While I attended a seminar in Freiburg this summer, I spent as much time as I could in the local coffeeshops and cafes surrounding the university, located in the Altstadt. One in particular suited me: Kaffee Kolben Akademie. Two rooms with a pastry shop at the front and a coffee bar at the back, standing tables and counters around the walls, with newspapers laid about for public use. Go ahead, click on the link. It takes you inside. This story is about something that happened there that day, involving three languages, Rilke’s poetry and a woman named Brigitte.

I was having a coffee and reading a paper one morning before class while a conversation began behind me, in which a local woman and a group of French tourists were discussing in French and German the possibilities for an enjoyable weekend excursion in the nearby vicinity. At first, while I perused the German paper, I caught a few words in French which I recognized, and began to listen more closely to see whether or not I could understand anything of what was being said. I was initially fascinated with the sounds of the place, the voices, the clink of the dishes, the whirring espresso grinders, the coins scraping across the counters, and the clatter of cups and saucers behind the bar. Out of the blur of sound, a few meaningful words and phrases would occasionally arise in both French and German, and as they ran together, I began to be able to gather a sense of the thread of conversation running behind me between the tourists and the elderly woman from Freiburg, whose spritely voice moved back and forth between languages most charmingly. I could discern that she had asked them in French where they had come from and if they spoke a little German. Then in German, she began to recommend a cycling route of the nearby area and as the tourists discussed the possibility, the conversation moved back into French, but as she interacted with them again with follow-up questions, it moved into German and then back into French with details about which tram to take. This woman’s voice was a stream of sound, which I followed carefully, picking my way after her, striving to catch her fluency and how she switched so skillfully back and forth between languages. In the end, I understood that she was recommending to them an itinerary involving a tram ride to a bike station, a bike route to a hiking path, and then a hike up the mountain Schauinsland, a nearby landmark, followed up by wine drinking, listening to music and dancing afterwards. It was actually kind of complicated for a single day’s excursion, but she apparently thought this was definitely the way to spend a free day in Freiburg. After a repetition of the different parts of her instructions and a flutter of well-wishing, she bid them farewell and began looking through the news paper at the table.

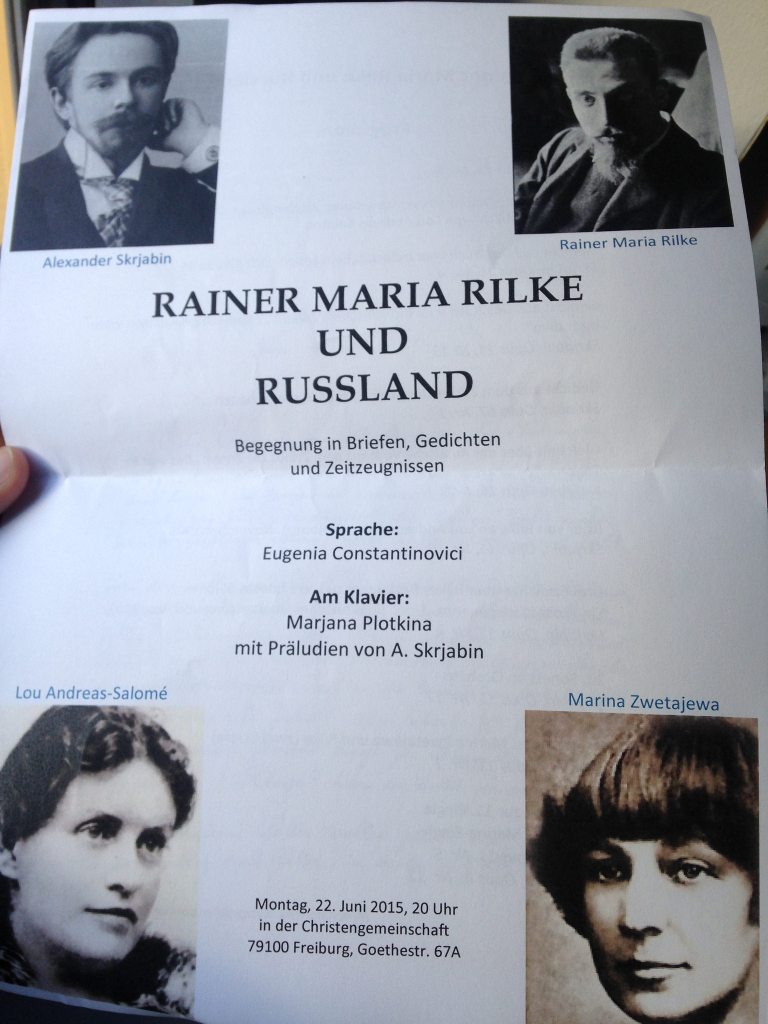

It was at this point that I enter the story, for as she looked through the paper, she came across a notice about a poetry reading to be given on the upcoming Tuesday evening in a local church, and she began asking the people around her if they knew where the church was located. No one could answer her question. She even turned to me, and in a gentle but inquisitive voice, asked me in German if I was familiar with the Goethestrasse in Freiburg. I replied in German, and in fact the whole of our conversation took place in German, but I will recount the story in English for you.

“Do you happen to know where the Christian fellowship of Goethestrasse 67 is located?”

“No, I’m sorry. I’m not familiar with the city. What’s taking place there?”

“It’s a poetry reading. “Rilke in Russia,” and it takes place at this church on this street on Tuesday.” She pointed to the notice in the paper. “But I’ve never heard of this church before.”

I was startled and curious about the poetry reading, because I had just checked out a book of poems by Rilke from the Goethe Institute library during my seminar and had been reading it in the evenings. “I’d like to go to this poetry reading.” I said to the woman. “I’m currently reading Rilke.”

“Are you!” She smiled at me. “Then we should go to this poetry reading together. How is it that you are reading Rilke? This evening reading will be of some of his poems and his writings which he wrote while he was traveling in Russia.”

Having spent some time in Russia as a teenager, and being something of a traveler myself, this made the event all the more appealing to me. I did not know that Rilke had spent time in Russia. I introduced myself to the woman, extending my hand. “My name is Sasha.”

“I am Brigitte,” she grasped my hand and shook it firmly with a smile on her face. “Are you really reading Rilke?”

“I have a poem of his which I’ve written down because it was so beautiful.” I reached for my journal. “Would you like to see it?”

“Of course!”

But my thin, penciled handwriting was too cryptic for her eyes, and she asked me to read it aloud. Amidst all the sounds of the coffee shop, I read the poem in a clear voice, pronouncing the words slowly and making eye contact to discern whether or not she could hear me. It was one of the most tender poems I had come across, and so I felt a strong sensation of vulnerability as I read it, but something held me to the act and erased any tension. Here was a real audience, someone who wanted to hear poetry from a stranger in a crowded coffee house. I will give my meager translation of Rilke’s poem, Schlaflied (lullaby), which I read to Brigitte.

Once I lose you, will you be able to sleep, without me whispering over you like a crown of lime leaves?

Without me here, awake, laying words like eyelashes upon your breast, upon your arms and upon your legs, upon your mouth?

Without me closing you up and leaving you alone with yourself, like a garden full of melissa and star-anise?

“Oh, that is so beautiful!” she cried. “I’ve never heard that one before. Will you write down the name of it in my little book?” And, I swear, she took out a little black leather book with narrow lines and I dutifully wrote down the name of the poem and Rilke’s name next to it. “We must go to the reading together. Have you heard Rilke’s “Werkleute sind wir?” I hadn’t, and she began to recite parts of it to me, recounting the lines freely from memory, closing her eyes and smiling, then opening them again and looking at me, speaking line by line until she had finished.

“I don’t know that one” I replied, enchanted by this fair, old poetess, spinning her charms around me.

“Ah, I recite poetry. I have for years. And I know the piano accompanist who will be at this reading. I know her personally. She has a four-year-old child. Rilke in Russia, yes. Will you write down the address for me in my book? I don’t have anything with me. And we will see each other again there.”

I wrote down the street and the address and the date. “Do you have all the information?” I asked her. She looked at what I had written. “Yes. Oh, and 8:00. There, yes. That’s it.” She looked at me again as she closed up her book and put it in her bag. “Sasha. Such a pretty name. We’ll see each other at that place. My daughter studied German literature. She’s about your age.”

“I also studied German literature.”

“What? Really? And what do you do now?”

“I teach.”

“Where?”

“In Alaska, actually.”

“In Alaska?”

“At the Rilke Schule. That’s what my school is called. That’s why I was reading the book of Rilke poetry.”

“In Alaska! Oh, how fantastic. But this school…does it have some kind of guiding principle..is it just called Rilke Schule or has Rilke been transported there in some way?” I loved how she phrased this question, for I imagined the spirit of this sensitive poet of love lyrics rising from the spruce trees surrounding our school grounds in a sudden and ridiculous image.

“We learn–well, the children learn poems.”

“By Rilke?”

“Yes, by heart.”

“Is that not too difficult?”

I laughed softly, remembering how many of my own students had memorized “Erlkönig” and recited it freely for the founder of our school, who had come by for a visit to my classroom one day. They had broken into it suddenly, as she prompted them with the first line, and all twelve of them began to chant it in its entirety, with emotion and speeding up in the exciting portion and slowing down at the sad parts.

“Our hero, I mean, our mascot, is the panther.” I mentioned to her. One of Rilke’s most famous poems, which is also part of our school poetry contest for the middle school level, is “Der Panther.” I had no idea when I mentioned this detail how it would affect Brigitte or what it would stir inside her. Her face changed and her mouth formed a small O.

“It would be “Der Panther,” she said softly, almost to herself.

“Do you know it?” I asked her.

“Yes.”

“The children learn it by heart.”

She looked at me for a moment. Something I said had caught her ear. “Are you French?” She looked at me quizzically.

“No, I’m American.”

“Ah, well then, you speak English.” She made this last comment in English, and then returned to German. “So then, the Americans know about something like this. “Der Panther.” Hmmm!” And without losing a moment’s momentum, she began to share her story with me, the thread of Rilke and the panther poem and recitation that connected us and bound us mysteriously, strangers though we were. “My mother died at 98 years, my mother did, and beginning when she was 94, I had to recite “Der Panther” for her every day. “I’d like to have “Der Panther” now,” she would say to me. Do you know it?”

And then, holding my gaze with a steady eye, and standing less than an arm’s breadth from me, Brigitte began to recite the poem that she had recited to her dying mother every day in her last years, a poem about exhaustion and being caged, feelings of isolation and distance; this she recited to me in its totality, without breaking eye contact but adding small comments about her mother, in the midst of that crowded coffeehouse in Freiburg, while the people around us sipped their espressos and paged through the papers and chattered and laughed and clattered their cups and spoons.

His vision, from the constantly passing bars

has grown so weary that it cannot hold

anything else. It seems to him there are

a thousand bars; and behind the bars, no world.

As he paces in cramped circles, over and over,

the movement of his powerful soft strides

is like a ritual dance around a center

in which a mighty will stands paralyzed.

Only at times, the curtain of the pupils

lifts, quietly–An image enters in,

rushes down through the tense, arrested muscles,

plunges into the heart and is gone.

Brigitte closed her eyes a moment, then opened them at looked into mine. “That was the poem of my mother. She was 94 then. That was when she said, “Speak The Panther to me! Every morning! And then she became…she became tired. She was tired.”

“And she also loved poetry.” I smiled.

“Ah, my mother, she worked so hard…”

“And she taught you the love of poetry. And literature.”

Brigitte held my gaze a moment, then snapped with energy. “I’m coming to Alaska! And this Rilke Schule. How do you get to this place? How do you get to Alaska? How do you get there? How far is it?” It was as though she had been jerked free of something which had held her fast, and she looked at me with with sparkling eyes and a smile played around the corners of her mouth. Curiosity hummed through her.

“It was six hours by airplane until Iceland.”

She nodded. “Iceland, yes.”

“Then five hours to Zürich.”

“Zürich, yes.”

“And then by train.”

“By train, how long is that?”

“Two or three hours.”

“So, yes. Certainly very beautiful. One must go in summer to Alaska, yes? It’s something special. Oh, how magnificent!” Actually, what she said was “Ach, wie super-toll-nett!” which is something like “super-fantastic-nice!”

I wanted to tell her a little more about my school. “But this school–”

“The Rilke Schule?”

“Yes, in our school the children learn German from kindergarten until the eighth grade.”

“Yes.”

“Half of the day is German, and half of the day is English.”

“Yes, English, of course.”

“And then they learn French.”

“Oh, French! Ça çe bien! Oh, that is fantastic. And we came to know each other over this one name, “Rilke!” She clasped my hand. “I am looking forward to the evening, and you will get to meet the pianist who has accompanied me at concerts. I recite poetry at concerts, did you know? We do music, songs and poetry. And we have our next concert on the seventh of July in Lörrach. We have all our concerts in the garden.”

I thought quickly. I would be in Switzerland at that time, but it would be possible for me to come to Lörrach. “In July?”

“In July in Lörrach.”

“I could be there.”

“If you like. It’s in a home for the elderly. The Margareteheim for the elderly. Do you know, they don’t have any memory any more. And our program is Goethe this month. I will introduce you to the pianist. We will stay in contact! Write down your telephone number. Do you have something to write with? I have nothing.”

My heart sank. I had a phone, but no service in Europe, and there was no way for Brigitte to call me. However, I hoped that if she and I both attended the poetry reading, we would see each other there.

“My telephone number doesn’t work.”

“It’s doesn’t matter.” She brushed the problem aside with a wave of her hand. “Just your name then. And I will introduce you to the one who plays the piano. I’m looking forward to it, Sasha! So sweet! And your company as well. It revived me. It does me good. It gives me strength today. Yes, bye-bye, Sasha!”

And she was gone from the cafe and I was standing there, holding my journal and the newspaper and wondering if I really would see her there. I gathered my things, left the cafe and walked to class at the Goethe Institute.

On that Tuesday, I prepared to attend the evening’s poetry reading. My class traveled to Strassbourg in the morning, and when we arrived back in Freiburg, I had only just enough time to make it to the poetry reading on the other side of town if I took precisely the right tram or walked very, very quickly and didn’t get lost. I had left my bicycle back at the guesthouse, and I wasn’t sure which tram to take, so I just walked as fast as I could in the most direct path to the little Christian church at Goethestrasse 67a on the east side of the river.

I arrived after it had begun, took a program from a stool and entered through a large wooden door which I closed behind me with an unfortunate little bang, but I quickly moved to a seat in the back row and sat perfectly motionless. About 40 people, middle-aged and older, had gathered in chairs before a small stage, where a woman sat reading from a stand. When she finished, a pianist played a short piece and was followed by another reading, usually with some kind of introduction. The reader shared both poetry and prose by Rilke written during his travels in Russia, as well as a poem which he had written in Russian (with German translation), but most interestingly, she read brief sections of love letters which were exchanged between Rilke and the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, who was very much in love with Rilke. I did not see Brigitte anywhere in the audience.

After the program ended, I watched the people file out, but she was nowhere to be seen. I was not introduced to the pianist. I walked home in the dark, words of Germany poetry and love letters echoing in my mind, wondering what had become of Brigitte.

P.S. Later, when I recounted the first part of this story to a dear friend, he wrote back to me, “Maybe you met a older version of yourself that day. The Sasha who decided to stay in Europe.” That was perhaps the best response I think I could have received.

“The Margaretenheim for the elderly. Do you know, they don’t have any memory any more. And our program is Goethe this month.”

I wonder… is Brigitte carrying on the work she breathed into life at her mother’s request, of speaking for those who still have much to say, but no memory to put it into proper form? How hard that work must be sometimes. I wonder what associations you revived for her which gave her a renewed strength and sense of purpose. Was it an opportunity to reflect on her mother? People are so inventive. We can contribute such small things, simple observations, innocent expressions, a gesture of kindness, a glimmer of empathy, a widow’s mite, and those who receive them take these tiny pieces and fashion them into spiritual monoliths.

LikeLike

It was a special exchange that day. Completely unexpected.

LikeLike